Advanced civilization at the foot of the fire volcano

- Hilda Steinkamp

- 1 day ago

- 5 min read

Pompeii's ruins tell vivid stories - Part 2

Highly developed urban culture

Pompeii Antica was a structured community. This applies to the infrastructure, with its grid-like street network, as well as to the administration. The estimated 15,000-20,000 inhabitants were mostly wealthy, enthusiastic about luxury and entertainment, and full of joie de vivre and a zest for life. The settlement, situated on a plateau, was heavily fortified with city walls, eight gates, and eleven watchtowers. Two thousand Roman veterans further enhanced security. Pompeii—protected against people, not against a volcanic force of nature.

The Foro (4th century BC) and its adjacent buildings formed the communal center for civic gatherings, trade, justice, and religious worship.

At the polling station, free men registered for the annual local elections. Graffiti on the walls advertised for candidates.

In a stately residence (2nd century BC) lived one of the two elected chief administrators, a kind of Lord Mayor with judicial powers. As the cultured host in the Casa del Fauno (see the bronze figure of a dancing satyr in the courtyard), fluent in Latin, he received citizens in the public area, separate from his luxurious private quarters with their own baths.

Pompeii's temples were rooted in the tradition of the Greek polytheistic cult. Zeus (Latin: Iuppiter, Italian: Giove ), the Roman state god and ruler of the sky and weather, and his son Apollo, god of prophecy, among other things, were highly revered. Belief in gods remained a spiritual luxury in Pompeii's history; it offered no protection against the raw power of the volcano.

Early Roman emperors were denied godlike status. Thus, the cult site Tempio del Genio di Augusti was not dedicated to the person of the first emperor Augustus and his successors, but to their statesmanlike spirit.

TheTempio della Fortuna Augusta bears a similarly secular title, praising the good luck (fortuna) that the emperor(s) had in increasing the prosperity and stability of the empire. Today, free-roaming cats appreciate the ruins as a hunting ground.

The community also took care of everyday needs. The commercial laundry was run by men. This is indicated by the occupational name "fullones" (washermen), the owner's name "Stephanus," and frescoes depicting men washing clothes and enjoying their leisure time.

Strade, fontane, fognature

Roads, fountains, and the sewer system – three good reasons for the size and stability of the Roman Empire. So say ancient historians. The same applies to Pompeii.

Founded around 600 BC and subject to changing foreign rule, the town experienced its heyday from 80 BC onwards as a Roman colony. Situated on the Sarno River and the Gulf of Naples, it developed into a flourishing Roman trading town and attractive summer resort . Merchants and craftsmen – along with landowners – enjoyed high social standing in Roman times.

Pompeii benefited from Rome's hydraulic engineering skills. Underground aqueducts fed thermal baths as well as watercourses in public buildings and private homes. A Roman-style fountain system at every major intersection provided citizens with high-quality drinking water. Some reconstructed fountains still flow today – for thirsty tourists wandering through the vast archeological area.

Road construction and sewage systems go hand in hand. Pompeii's streets had a stable basalt pavement. Deep ruts left by cart wheels on the blocks testify to their centuries-long durability.

The gently curved basalt surface channeled rainwater and wastewater into the gutter on both sides. Raised stepping stones allowed residents to cross the street with dry feet – like a zebra crossing. The carefully planned gaps between the stepping stones enabled cart or chariot wheels to pass smoothly.

Cenere - Under volcanic ashes

... Pompeii was buried in 79 AD. A severe earthquake earlier (62 AD) served as a warning, but was ignored, as Mount Vesuvius had been considered extinct since its last eruption around 800 BC. Then, on August 24th, it erupted again with explosive force at midday. The blast hit the southeast, where Pompeii, Oplontis, and Stabiae were located, while Herculaneum in the southwest was less severely affected.

A kilometer-high eruption column of ash and pumice was followed by streams of fire and ashfall. Boulders hurtled toward the earth at 200 km/h. No roof could withstand that. Pompeians fled, others stayed. After five hours, a 50 cm layer of ash covered Pompeii's destroyed houses. By midnight, the eruption column was 30 km high, and streams of heavy material and pyroclastic flows flooded the city, burying the last survivors. By the next morning, Pompeii had found its grave under a layer of ash and rock up to 20 meters thick.

Even the eyewitness account of Pliny the Younger, 25 years after the natural disaster, did not permanently anchor the city in the cultural memory of posterity. Vanished from the face of the earth. Forgotten.

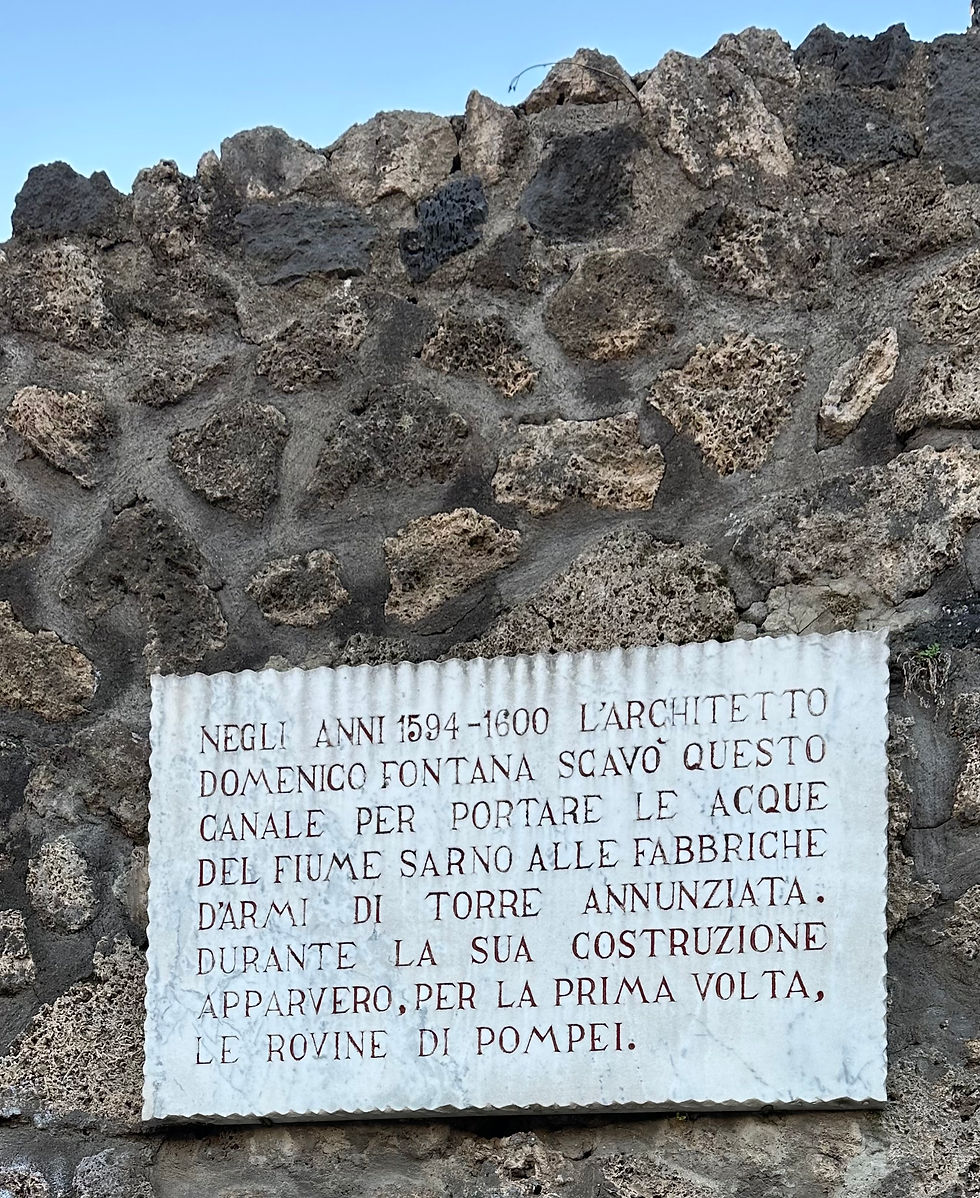

It wasn't until the end of the 16th century that the architect Domenico Fontana, while building a canal to transport river water from the Sarno to Torre Annunziata (formerly Oplontis), came across the first ruins of the sunken city.

Systematic excavations began in the mid-18th century and continue to this day. The Parco Archeologico di Pompeii is an ongoing project to reconstruct a buried, yet remarkably well-preserved urban culture, which has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1997. Bringing Pompeii back to life is the clear commitment conveyed by the work and banners at the excavation site.

A third of the ancient city still lies buried under volcanic ash covered with turf.

Pompeii's old and young dead

Pre-Christian burial in Rome, as in Pompeii, took place through cremation in mausoleums outside the city walls:

Some 1800 years after Pompeii was buried, the leading archaeologist Giuseppe Fiorelli (1823-1896) brought the most recent victims of Pompeii to light using a special technique. The decomposing bodies left cavities in the solidified lava. He filled these cavities with liquid plaster. The plaster casts (calchi) show the form and posture of Pompeians fleeing the lava flows and at the moment of their death by fire or suffocation.

There are believed to be at least 2000 victims of the volcano; half have been excavated so far.

The Sleeping Fire Mountain

Vesuvio remains dangerous. In the 16th century, it was considered extinct. In 1631, the strongest eruption since the destruction of Pompeii occurred. In 1929 and 1944, it once again demonstrated its Indo-European name, "the burning one." Pyroclastic flows buried entire villages.

Since the 1970s, Naples has been trying to protect its densely populated region from further volcanic eruptions. However, the building ban in the so-called "red zone" is countered by high housing demand and the economic interests of urban development. In the satellite city of Pianura, west of Naples, 60,000 people live in illegally constructed and poorly protected houses.

The magma chamber of Mount Vesuvius could reawaken at any time. For now, only fumaroles rise from the crater – water vapor and volcanic gases, as volcanologists from the Vesuvian Observatory in Naples reassure us. Perhaps these are the ones I discovered during the steep climb to the crater rim at 1200 meters?

"Look at this city!"

At the foot of the excavation site lies modern Pompeii with its 23,000 inhabitants.

A bronze figure by the Polish artist Igor Mitoraj gazes down at modern Pompeii. A powerless, athletic javelin thrower, without hands or feet. Embedded in its loins and shoulders are two head casts, like those from Fiorelli's plaster gallery. Mitoraj's trademark. And his helpless plea: "Look at this city!" A dance on the lip of the volcano.

The reawakening of Pompeii -

There's still so much to see.

I need to go there again...

Comments